|

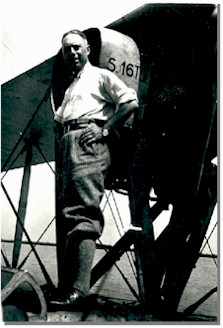

Pinedo’

s 1925 flight to Tokyo had its origins in an analysis of Arturo Ferrarin's

earlier journey, in which the pilot speculated that while aircraft had

endured admirably, a seaplane might have been better suited for the journey.

By late 1924, Pinedo had requested and received permission to take leave

of office and attempt his own tour of the Orient. But he didn't intend

to simply duplicate Ferrarin's feat with a different type of aircraft.

Pinedo's voyage would cover a record shattering 34,000 miles as he blazed

a trail to Australia as well. Pinedo’

s 1925 flight to Tokyo had its origins in an analysis of Arturo Ferrarin's

earlier journey, in which the pilot speculated that while aircraft had

endured admirably, a seaplane might have been better suited for the journey.

By late 1924, Pinedo had requested and received permission to take leave

of office and attempt his own tour of the Orient. But he didn't intend

to simply duplicate Ferrarin's feat with a different type of aircraft.

Pinedo's voyage would cover a record shattering 34,000 miles as he blazed

a trail to Australia as well.

The aircraft he selected was a Savoia S-16ter, a five-seater biplane of the type being built at the time for the Royal Italian Navy. He removed three of the seats to make room for additional supplies and fuel, and christened the plane the Gennariello, after San Gennaro, patron of his beloved Naples. Arrangements were made with Shell Oil Company, the British government, and local authorities for refueling along the way. With all preparations in place, Pinedo and his companion, mechanic Ernesto Campanelli took off from the S.I.A.I. plant at Sesto Calende into the rainy, predawn skies of April 20th, 1925. |

|||

| Lost motor oil was replenished with forty bottles of castor oil... |

Pinedo had spent a considerable amount of time planning the voyage, studying the normal weather patterns of the regions through which he intended to pass, and plotting his route accordingly to minimize hazards. But destiny had no thought of making the going easy. Campanelli's stock of spare parts, necessarily limited by weight considerations, was not always sufficient to handle on the spot repairs. In every such instance, the mechanic was obliged to call his resourcefulness into play and fashion makeshift parts out of whatever was on hand in the exotic locales where the Gennariello had touched down. A copper frying pan obtained from a kitchen in Baghdad provided the metal to patch a leaking oil tank. When an engine seal ruptured, a new one was cut from a pair of leggings. Lost motor oil was replenished with forty bottles of castor oil bartered at a marketplace in Dummagudin, India. |

|||

| AUSTRALIA |

Gradually nudged off schedule by unforeseen layovers due to bad weather or lengthy repairs, their arrival in Indochina coincided with the start of the monsoon season. The Gennariello's open cockpit offered the no refuge from the elements as the aviators battled near-constant rain and gale-strength winds. But plane and crew endured until they reached the Australian coast on May 31st. Their tour, a virtual circumnavigation of the continent, which included visits to Melbourne, Sidney and Brisbane, was completed by the second week of August. Upon departing, Pinedo could claim to have piloted the first seaplane there from Europe, and the first plane of any type which had not only managed to reach Australia from such a distance, but had transversed that massive land and then proceeded onward. |

|||

| JAPAN |

(Only two airplanes had preceded the Gennariello from Europe to Australia; In 1919, the Fifth Continent was reached with a Vickers Vimy by a four-man Australian crew after a 28 day journey from England. A second, though somewhat faltering, flight was made there the following year in a De Havilland DH 9 by an Australian and a Scot, again with England as the starting point. In both previous instances, of course, Australia was the final destination as opposed to being one segment of a much broader itinerary, as in Pinedo's case) His next "first" would be opening the first air route between Australia and Japan, a feat he completed when the Gennariello landed at Tokyo on September 26th. A welcome every bit as clamorous as the one given to Ferrarin five years earlier awaited Pinedo and Campanelli upon their arrival. For a solid week, the Japanese showered them with honors, lavish eulogies and all the gifts their plane could carry. Then, after the Gennariello had been fitted with a replacement engine, the Italians returned to the sky for home. |

|||

| ...like a victorious Caesar returning from his conquests amid the wildly cheering citizens of Rome |

On November 7th, Pinedo brought down his well-weathered aircraft upon the lazy, brown waters of the Tiber, like a victorious Caesar returning from his conquests amid the wildly cheering citizens of Rome. Mussolini, quick to utilize such parallels, lionized the airman as the paragon civus romanus, one of the new Italic breed who were destined restore the imperial Latin glories of the past. Silent diligence was expected of such 20th century legionnaires, and for this Pinedo's laconic manner was made to order. But the sparse comments offered by the aviator at the press conferences that followed his return were due more to his tendency toward shyness and to the curious conviction that talking too much brought bad luck. Incongruously, Pinedo allowed superstitions more suited to an 18th century Neapolitan fisherman than a modern, educated military officer to dwell in a corner of his otherwise pragmatic mind. He shunned publicity and spoke sparingly about his exploits to reporters for fear of provoking future misfortune. |

|||

| Pinedo's taciturnity even tried Mussolini’s patience |

Pinedo's taciturnity even tried Mussolini’s patience. Before embarking on his journey, the aviator had been given orders to keep his superiors notified of his progress, but his compliance extended no further than dashing off telegrams to Rome that briefly stated his latest point of arrival. The single word brevity of the reports was annoying to Mussolini, who had to rely on newspaper articles to learn what Pinedo was actually doing. Upon reaching Tokyo, Pinedo was presented with stern instructions from his government to wire a full and detailed account of the flight at once. The aviator's reply, his longest communication yet, was classic. "Finished 2nd part of journey. Arrived late owing to grave difficulties in Zamboanca-Tensui region due to storms and strain on motor. Machine and crew in excellent condition. Am overhauling machine. Will wire when ready to return” |

|||

| AMERICA | Pinedo’s second, great journey was based on a suggestion by Benito Mussolini, who saw the need to promote a sense of national pride among those Italians who had emigrated abroad, particularly to the Anglo-Saxon nations of North America. | |||

| would win a place in the record books for all time |

Pinedo subsequently sketched out a route that would begin with an Atlantic crossing to Brazil. From here he would proceed with a lengthy tour of South America, peppering up the trip with a daring, exploratory flight over the Brazilian jungles. From there he would make his way to North America, visit major U.S. and Canadian cities, then wrap up the voyage with a second Atlantic crossing back to Italy. The variations in climates and topography covered in the course of the journey would satisfy Pinedo's original purpose of demonstrating the versatile durability of an Italian seaplane, and the round trip ocean crossing, never before accomplished, would win a place in the record books for all time. The proposal won Mussolini's wholehearted backing, and Italo Balbo, the Air Ministry's newly appointed Undersecretary, was instructed to give the project unlimited support. |

|||

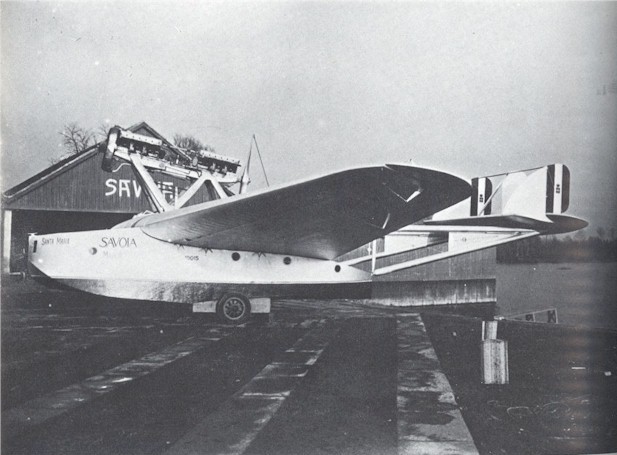

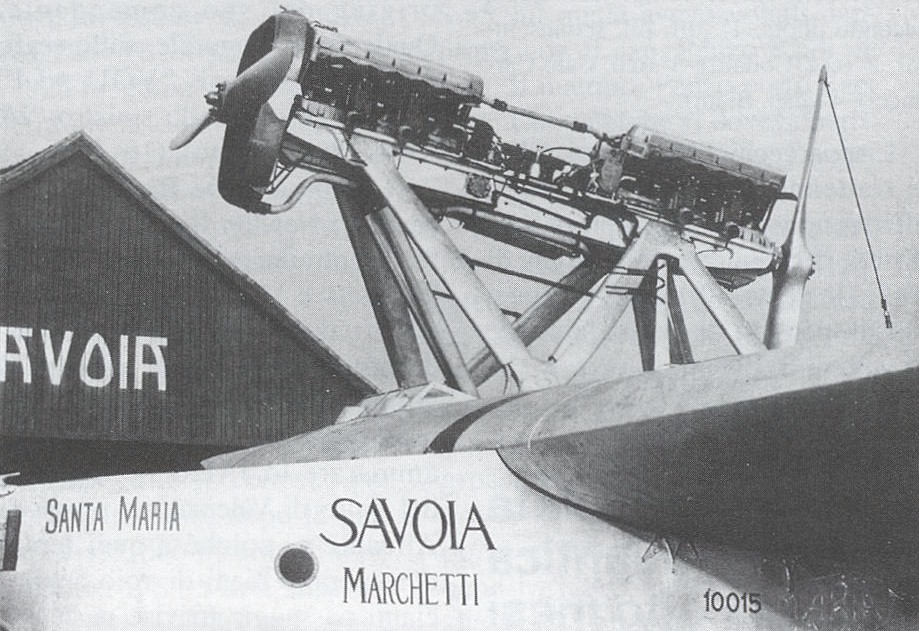

| ...employ an S-55 flying boat originally designed by Alessandro Marchetti |

In choosing his aircraft, Pinedo turned once again to the S.I.A.I. firm at Sesto Calende, which had supplied the rugged Gennariello for his Oriental tour. This time he opted to employ an S-55 flying boat originally designed by Alessandro Marchetti as a torpedo bomber for the Regia Aeronautica. Having recently captured fourteen world records in its class for speed, distance, altitude, and load capabilities, the aircraft had emerged as S.I.A.I.'s top of the line product. With its two, sleek hulls joined like Siamese twins by a single, broad and sweeping wing, even the plane's appearance was outstanding. The cockpit was situated in the center of the wing itself, above which was perched two tandem-mounted Isotta Fraschini V-6 engines capable of developing more than 1,000 H.P. In the way of accessories, the plane was equipped with top quality navigational instruments, a saltwater distiller, a life raft, and, with clever thoughtfulness, a complete array of fishing gear. |

|||

Captain Carlo Del Prete and crew |

The size of the S-55 afforded a three-man crew, and de Pinedo enlisted his old navy comrade and navigation expert Captain Carlo Del Prete and mechanical trouble-shooter Sgt. Vitale Zacchetti to accompany him on the flight. But the voyage called for special considerations, even for a machine as exceptional as the S-55, which, of course, hadn't been designed as a long-distance touring vehicle. The advantages of hefty engine power were naturally penalized by larger fuel consumption. To attend to this, de Pinedo had the plane fitted with tanks capable of holding more than a thousand gallons of gasoline. But now the additional weight posed potential take-off problems. To maintain a careful balance, the tightest route between points was positively essential. Consequently, the actual starting point for the ocean crossing was planned to be at Portuguese Guinea on Africa's jutting western coast, which offered the narrowest gap between the hemispheres. |

|||

the Santa Maria...   |

Construction of Pinedo's S-55 was completed on January 30th, 1927. The aircraft was christened the Santa Maria, and transferred to the southern tip of Sardegna. Balbo and several Regia Aeronautica officials arrived to preside over a brief, torchlight departure ceremony, and the Santa Maria soared off beneath the stars on the frigid, early morning hours of February 13th. Within hours, the aviators were skirting over the Algerian coast, and Morocco, the Gibraltar, and the desolate beaches of the Spanish Sahara. Here they spotted the bleached, eroding remains of two French airmail planes, their pilots slaughtered by bandits, and were reminded that the ravages of nature might not be the only perils ahead. A quick refueling stop was made at Villa Cisernos, and by 8 o'clock the following morning, the Santa Maria reached Bolama in Portughese Guinea. Here the Italians paused to prepare for their Atlantic crossing, set for February 16th, de Pinedo's 37th birthday. |

|||

|

The weather at Bolama was sweltering, and when the hour for departure arrived, broiling ambient temperatures caused the engines to rapidly overheat whenever the plane tried to pull itself off the surface. The Italians had no recourse but to lighten the machine by dumping a great quantity of gasoline. They then flew back north to the Cape Verde Islands, where cooler weather was reported. Take-off was managed on February 23rd, but only after the fuel load was limited to the calculated minimum required to get over the ocean, and every bit of excess weight, meaning the crew's luggage and almost anything else that wasn't absolutely essential, was shed from the aircraft. |

||||

| ...that would bring him, like Columbus, to the shores of the New World. |

Once in the sky, de Pinedo entrusted the Santa Maria to the gentle guidance of the tradewinds that would bring him, like Columbus, to the shores of the New World. Cruising pleasantly along, the crew relaxed and uncorked a bottle of red wine. They were permitted brief repose. Nearing the equator as they cut their diagonal path toward Brazil, the Italians soon found themselves immersed in a ferocious squall. Rain poured down so heavily upon the aircraft that Pinedo likened the experience to flying through a waterfall. |

|||

|

Unable to surmount the storm, the Santa Maria hugged low to the ocean surface, dropping a mere 150 feet above the waves. But there was more to contend with than rough weather. Once again, the cooling system temperature began climbing at a fearful rate until billows of steam were hissing from the radiator. Fresh water evaporated as fast as Zacchetti pumped it in from the reserve tank, and this supply was soon exhausted. He then turned to mineral water from the crew's provisions, and when that was gone, to rain water sopped up with a sponge and collected in buckets! |

||||

|

Zacchetti's dilligence gradually reduced the engine temperature to a safe level, the storm tamed down to a drizzle, and the Santa Maria proceeded onward without further incident. At about 3 pm, the Italians spotted Fernando de Noronha Island, indicating that the South American continent was only 270 miles ahead. As they proceeded onward, the storm returned, growing worse as the final hours of their journey passed. By the time the Brazilian port of Natal came in sight, the wind and waves had turned so turbulent that Pinedo decided to double back for Fernando de Noronha rather than risk damaging his plane in a rough landing. His precaution paid no dividends. The waves were just as choppy at the island, but now, his fuel supply nearly spent, Pinedo had no choice but to bring the Santa Maria down. |

||||

|

Once on the surface, the Italians exchanged signals with the nearby Brazilian cruiser Barroso, which was approaching to tow them to port. The heaving waves made it impossible for boats to be dropped to reach the plane, and the Santa Maria could be secured only by tossing ropes from the deck of the steamship. To do this, the ship had to move in dangerously close to the bouncing aircraft, and in the process of linking up, the two vessels slammed into each other. |

||||

|

Pinedo cringed at the horrid sound of the collision. The S-55's right aileron was in splinters, and the Brazilians, all apologetic, took every possible measure to assist in its immediate repair. In less than twenty four hours, the plane was restored and the Italians were on their way. By four o'clock the following afternoon they reached Natal, and from there they began their American tour. |

||||

| ...showed the Italians such a good time that they were reluctant to leave. |

Working their way southward, the aviators made landings at major Brazilian ports, their arrivals invariably marked by parades, banquets, and general merry-making. Rio de Janiero welcomed them with its most festive, carnival atmosphere and showed the Italians such a good time that they were reluctant to leave. A regiment of policemen had to rescue the flyers when they were nearly smothered by a sea of cheering admirers upon disembarking at Buenos Aires. |

|||

|

After an equally frenzied reception at Montevideo, they proceeded inland to Assuncion, where city officials ordered the closing of schools and businesses to properly celebrate the event. The festivities culminated with the official name-changing of a downtown avenue to Rua F. de Pinedo. |

||||

| The Neapolitan

was indisputably the man of

the hour. |

The Neapolitan was indisputably the man of the hour. Although never really comfortable in the role of celebrity, he sportingly sat through dozens of interviews, signed thousands of autographs, and made countless speeches in which he extolled the virtues of the seaplane and its future role in intercontenental air travel. That the soft-spoken Pinedo was no fiery, gesticulating Mussolini at the podium did not mean yawning audiences. Instead, his concise but genial way of speaking, in stark contrast to his daring exploits, only confirmed his reputation as a composed and courageous hero. |

|||

|

Considering what he and his companions were about to attempt, their bravery could hardly be doubted. Waiting for them like a grim netherworld as they began their northward advance across the continent was Brazil's vast Matto Grosso region, the densest jungles in the hemisphere. Few Europeans, and certainly none in airplanes, had ever penetrated the entire extent of this tangled wilderness, where civilization was restricted to a handful of sparse outposts. Scattered tribes of indigenous peoples, some known to be unfriendly to intruders and most of them yet to advance beyond the stone age, were the region's chief inhabitants. Those outsiders impertinent enough to invade the Matto Grosso were often never heard from again. Such a fate had befallen an expedition led by the capable and experienced British explorer Percy Fawcett only two years previous. |

||||

|

While Brazilian authorities had guaranteed the availability of fuel in the settlements and villages along the route, the Italians knew that they couldn't count on ready assistance once they penetrated the dark rain forests. Equipped with a only set of river maps of questionable accuracy, they began their flight through the Matto Grosso on March 16th. Pinedo's strategy was to follow the Paraguay River to the Guapore and Madiera Rivers, which snaked their way ever northward toward the Amazon basin. Once underway, it became clear that this simple plan wouldn't be so simple to follow. Surrounding vegetation was so thick that it was all but impossible to distinguish the waterways from above, and the Italians had to limit their altitude to just a few feet over the treetops to stay on course. Landing was utterly impossible under such circumstances, and the aviators could only ask Providence to spare them any reason to have to attempt a descent. |

||||

|

To their relief, a clearing came into view as they approached the village of Sao Luis de Caceres, some thirteen hundred miles north of Assuncion. The plane needed fuel, so the Italians gratefully seized the moment and ducked under the branches to the Paraguays's vine and tree trunk-crowded surface. Even as they were still skimming down upon the river, it was clear that their troubles were scarcely over. Besides having to contend with an obstacle course of dangling vines and low-slung branches, the aviators saw that the river's twisting course simply did not provide a long or straight enough stretch on which to accelerate to a take off. |

||||

| Pinedo

hired a passing

boat to tow his plane to a suitable takeoff point. |

The S-55 was refueled at the village dock only to flounder on the Paraguay until Pinedo hired a passing boat to tow his plane to a suitable takeoff point. But to the crew's misery, it took several hot and dreadful days to find one. While the Santa Maria was hauled along over the meandering river, the Italians spent their hours staving off a constant assault by mosquitoes and flies. Del Prete found it helpful to snap on a pair of rubber gloves to protect his hands from insect bites, and the three men took their meals in shifts, one eating while his companions blasted bugs away with sprays of kerosene. At one point, Pinedo suggested seeking relief from the oppressive heat by taking a swim, only to prudently change his mind upon spotting the menacing eyes of an alligator. This brought gales of laughter from the Brazilian boatmen, who advised the Italians of far more treacherous dangers lurking below. Alligators, they merrily explained, at least can be seen. It's the pirana, the tiny razor-toothed fish, that one must really fear in these waters. Fascinated, Pinedo later worked an experiment by tying a piece of meat to a string and dropping it under the surface. Feeling a tug, he jerked it up and brought up several piranas clamped tightly to the bait. |

|||

|

Just before midnight on March 18th, after covering two hundred slow and weary miles, the Santa Maria was brought at last to a stretch of water sufficiently long and clear to permit an unhindered take off. The Italians bedded down for the night, but at the first hint of dawn, they were soaring out of their oppressive, jungle prison and into the refreshing coolness of the open skies. |

||||

| No humans had ever before appraised the wondrous immensity of these rain forests from the air |

No humans had ever before appraised the wondrous immensity of these rain forests from the air, and the crew marveled at the unending, deep green blanket that sprawled beneath them toward every horizon. Cutting over to the Guapore River, they could discern the majestic peaks of Bolivia looming up far to the west, the continuity of the gray slopes occasionally breached by thundering waterfalls. |

|||

|

After about seven hours, however, the crew's attention began turning from the magnificent panorama to the steadily dropping needle on their fuel gauge. With mounting concern, they searched for the refueling depot that the Brazilians were supposed to have set up for them along the river, but no sign of it was detected. Pushing on for another 350 miles, the Santa Maria coasted down at the village of Guajara Mirim just as the final drops of gasoline trickled from its tanks. |

||||

|

The impoverished residents of this tiny, malarial hamlet welcomed their visitors with a touching display of generosity, and enough gas was secured to put the plane back on course for the Madiera River. To repay their hospitality, Pinedo agreed to deliver a sack of mail from the town's post office so that humble Guajara Mirim could boast thereafter of being the first in the region to enjoy air mail service. |

||||

|

The Italians ran headfirst into a brutal thunderstorm as they proceeded on their jungle excursion, and had to escape its fury by making an impromptu descent on the rolling surface of the Madiera. Not to be undone, Pinedo and Del Prete, veteran sailors, managed to pilot the flying boat safely downstream until the rains slowed up enough for them to return to the air. |

||||

| ...a special performance of Madama Butterfly was given at the city's opera house in honor of the music-loving Pinedo |

On March 20th, they burst out of the jungle and landed at the city of Manaos in northeastern Brazil. Here the usual welcoming festivities awaited, but their first business in town was to march straight to church and give thanks for their survival through the mighty rain forests. A parade down streets strewn with flower petals and festooned with Italian flags followed Mass, and the celebration carried on well into the evening. That night, a special performance of Madama Butterfly was given at the city's opera house in honor of the music-loving Pinedo. But minutes after Pinedo sank into the thickly-upholstered chair reserved for him in the center of the house, he was lulled into deep slumber by Puccini's delicate melodies. Never having slept for more than four consecutive hours since he left Assuncion, the Neapolitan was simply exhausted. This fact was well known to his hosts, who looked on with gentle smiles even when his very audible snores began competing with the soprano on stage. |

|||

|

The next morning, the Santa Maria plunged back into the jungle tracing an eastward path over the Amazon River, bound for the city of Para near the Atlantic coast. While making the thousand mile run, the plane again flew into so violent a storm that its propellers were warped out of shape. Lightning bolts darted down within inches of the S-55, and the aircraft was bombarded by monstrous raindrops with the force of pelted rocks. Visibility deteriorated to nonexistence. The cockpit flooded. The engines shuddered and trembled, and building pressure perforated the overheated radiator in twenty spots. Only through relentless struggle were the Italians able to reach Para, the journey completed after eleven, punishing hours. Once safely docked at the city, Pinedo wearily inspected his plane's damage and confided to his companions his certainty that they wouldn't have survived had their ordeal lasted a half hour longer. |

||||

|

But the roughest part of their voyage was behind them, and the airmen had once again demonstrated their mettle. Three days later, well rested and their plane put back in shape, they were ready to take on the second half of their tour. On March 25th, they flew to Georgetown, Guyana, their final South American stop. The next day, they crossed the Carribbean Sea, making brief visits at Pointe-a-Pitre, Port-au-Prince, and Havana, where all the boats in the harbor sounded a chorus of bells and whistles for thirty minutes to greet them. Their next landing was at New Orleans. |

||||

| ...claiming for itself the distinction of being the first foreign airplane to fly to the United States. |

With swanlike grace, the Santa Maria touched down upon the Mississippi River on the afternoon of March 29th, claiming for itself the distinction of being the first foreign airplane to fly to the United States. While in South America, the Italians had replaced the wardrobes they had left behind on the beaches of Africa, Pinedo preferring golf suits to his Regia Aeronautica uniform, and were in the habit of making room in their cramped cockpit to wash and shave before landing at every major point. Expecting three haggard and disheveled wayfarers to stumble from the plane, Americans were surprised to see the trim, tanned, and well-groomed officers robustly stepping ashore in crisp clothes and polished shoes. |

|||

| "In ten years one would need only an airline ticket to repeat his travels." |

Reporters and photographers, Pinedo later recalled, swarmed about him as thickly as the mosquitoes of Matto Grosso, anxious to record anything he might utter. Asked about the significance of his exploits, he described his tour as but a preview of what would soon be common. In ten years, he assured, one would need only an airline ticket to repeat his travels. In response to the query of what sort of diet had sustained him through his adventures, Pinedo promptly replied that the Santa Maria was well stocked with the Italian staples of bread, cheese, and wine. Raised eyebrows at the mention of wine instantly reminded him of America's Prohibition laws, and he won laughs by hastily adding that his crew had been careful to polish off the last of their supply just before arriving in the States. |

|||

|

At the urging of their hosts, the Italians stayed on in New Orleans for the next several days, and when not attending the usual receptions and banquets, Pinedo spent his time answering the thick stack of congratulatory telegrams and invitations arriving from all parts of the country, examining maps and weather reports, and sitting down to swap stories and compare notes with his American counterparts. Interestingly, he took note of the plight of African Americans during his brief visit, and took time to make his own observations of their situation in New Orleans. He found this interesting enough to include a short section on the racial problems of the American South in his memoirs. |

||||

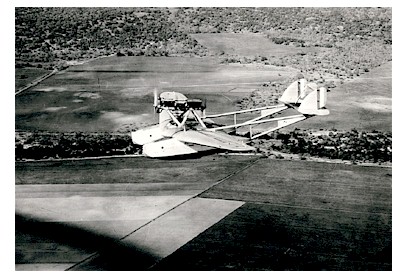

|

The U.S. tour got underway on April 2nd, with the Italians making a five hour flight to Galveston, then moving on to Lake Medina, at San Antonio. Over the next few days, their route took them along the course of the Rio Grande, into New Mexico, and over the Rockies, where they used the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks twisting around the peaks and crevices below as a guide map. By April 6th, they were cutting across Arizona. Pinedo expected to dock his plane at San Diego before the day's end, and his crew was looking forward to the grand reception being prepared for them there. |

|||

|

The business of a quick refueling had to be taken care of first, though, and at 10:14 on that sunny morning, the S-55 landed on Roosevelt Reservoir, a manmade lake some sixty miles east of Phoenix, where a depot had been set up for the job. A few local officials, including the state manager of the Standard Oil Company, Pinedo's fuel supplier, stood by to welcome the Italians. Pinedo was given a quick, walking tour of the reservoir's facilities, and then taken to the Apache Lodge, a nearby hotel where an informal luncheon was scheduled. As he and his hosts were entering the building, they heard a great commotion coming from the direction of the reservoir. "I turned toward the lake", Pinedo remembered, "and the blood curdled in my veins!”. A great wall of flames and rolling plumes of black smoke swelled up around his plane. The entire party darted to the scene, and the horror-struck Pinedo watched Del Prete and Zacchetti, who had been supervising the refueling, leap overboard to escape a fiery death. A frantic but futile effort was made to rescue the aircraft. Realizing the hopelessness as he saw his beloved plane reduced to a mass of crackling cinders, Pinedo turned to the crowd and desperately implored, "Somebody take some photographs! I want a final memory of my child!". |

|||

|

Gnawed by the flames, the engine supports collapsed and sent the engines plummeting sixty feet to the lake's floor. Within minutes, the only remnant of Pinedo's plans to conquer the American skies was the Santa Maria's smoldering bones bobbing wanly against the banks of the reservoir. |

||||

| ...the possibility of anti-Fascist sabotage was immediately suspected |

Since the tour was under Mussolini's auspices, the possibility of anti-Fascist sabotage was immediately suspected, especially after onlookers reported seeing someone fleeing from the scene just after the fire burst out. Henry Fletcher, the American ambassador at Rome, promptly assured Mussolini that if such was the case, the culprit would be apprehended and brought to justice. But it took only hours for Fred Paine, a reporter for the Arizona Republican to track down the fugitive, an 18 year old laborer named John Thomason who had volunteered to help with the refueling. The young man dolefully admitted responsibility for the disaster, having thoughtlessly discarded a lit cigarette into the water. Pools of gasoline floating on the surface ignited instantly, dooming the unfortunate Italian plane. |

|||

|

The fact that a single cigarette butt had destroyed the Santa Maria after it had survived 18,000 miles of nature's cruelest assaults was more than a little unsettling, but Pinedo accepted it's fate gracefully. He met privately with the remorseful Thomason, and returned to soothe fears of a diplomatic crisis by remarking to the press, "The misfortune which overtook the Santa Maria was the result of one, small boy's carelessness. In no way can the tragedy be connected to a plot. It was purely an accident, and I'm certain that my Government will view it in no other light (7)." Hours later, Mussolini issued a somewhat more elaborate statement declaring, "The interruption of Commander de Pinedo's flight, thus far so successfully carried out, wounds us most painfully. But while I have full confidence that Commander de Pinedo, despite this mishap, will be able to conduct his titanic venture to its conclusion, I wish to express full assurances that Italy, linked by such strong chains of friendship to America, sees absolutely no connection between this painful incident and the fact that it occurred on American soil." |

||||

San Diego, California |

His words diffused the tension, but as he indicated, Mussolini wasn't about to let the prestige that Fascist Italy had been garnishing by Pinedo's headline-winning tour come to such an inglorious end at a desolate lake in rural Arizona. Declining American offers to replace the aircraft, Italo Balbo ordered the construction of an exact duplicate and arranged for its shipment by boat to New York. In the meantime, Pinedo and his crew were flown to San Diego courtesy of the U.S. Navy, and from there proceeded by rail to the East Coast to await the replacement aircraft. As they crossed the breath of the country, the Italians paid visits to the major cities along the way, including Washington D.C., where they were greeted by President Coolidge, and a sumptuous, thousand-plate banquet was thrown for them. |

|||

| The infamous Sacco and Vanzetti case was still in the national spotlight |

Arriving in New York on April 25th, they were given an official welcome at city hall, during which the dapper and diminutive Mayor Jimmy Walker traded light-hearted jokes with Pinedo, expressing his delight at seeing that the famous aviator was "another little fellow" like himself. Of course, none welcomed the flyers more fervently wherever they went than the country's Italian communities. The infamous Sacco and Vanzetti case was still in the national spotlight, as were the illicit activities of men with names like Capone, Torrio, and Genna. Weary even then of being perceived as a race of anarchists, gangsters, and fruit peddlers, America's Italian population hailed Pinedo and his crew as powerful antidotes to these stereotypes. But there were others, opponents of Fascism, who regarded the flyers as propaganda puppets of the Mussolini regime, and objected to their very presence in the United States. Untoward scenes began to occur, the worst on the night of April 26th, when a riot involving an estimated twelve thousand people erupted as militant pro and anti-Fascists clashed outside a hall where the Pinedo was speaking. The aviator reacted with typical nonchalance to the disturbance, and complained bitterly only when Walker ordered constant police protection for him. With unhidden annoyance, he reminded his hosts that he had risked his life under far graver circumstances in the past, and he could not believe that anyone wished to personally harm him. |

|||

The Santa Maria II |

At 9:30 pm on May 1st, the Italian steamer Duilio arrived at Staten Island carrying the partially assembled Santa Maria II and a team of mechanics, technicians, and a heavily armed, stern-faced Fascist militia that kept round-the-clock surveillance over the machine. The plane was rushed to the National Guard airbase at Miller's Field for final assembly, overseen by Del Prete who boasted of the ability to rebuild the S-55 in his sleep. Tight security was maintained during the process, though reporters were permitted to view the aircraft from a distance of 75 feet. |

|||

| "post fata resurgo" |

With a sharp crack, a ribbon-laced bottle of mineral water, substituting the traditional, but outlawed champagne, was shattered against the bow of the fully assembled Santa Maria II at its christening celebration on May 8th. Pinedo studied his new plane and marveled at Balbo's thoroughness in duplicating its predecessor, even down to the most minute detail. The only detectable differences were autographs and notes of good wishes scribbled all over the hulls by workers from the Isotta-Fraschini and S.I.A.I. plants, and a most appropriate Latin inscription in the center of the wing, authorized by Balbo. It read POST FATA RESURGO ("I Arise After Death"), the motto of the mythological phoenix, which, consumed by fire, had risen from its own ashes. |

|||

|

A full month had been lost because of the Arizona incident, and ostensibly to return to Italy on schedule, Pinedo revised his itinerary by eliminating all points west of the Mississippi. But he had another good reason for wanting to speed things along. Perhaps sparked in part by his own exploits, interest in the Orteig Prize had sharply increased and the world's attention was focused on the North Atlantic, with a non-stop flight between America and France emerging as the big challenge of the moment. Activity in the competition had stepped up greatly during the weeks in which the Italians awaited their replacement aircraft, though all attempts thus far had had tragic conclusions. On April 26th, the American contenders Noel Davis and Stanton Wooster were killed when their Keystone Pathfinder crashed on takeoff. The veteran French pilots Charles Nungesser and Francois Coli, making their try on the very day of the new S-55's arrival at New York, simply vanished somewhere over the ocean and were never seen again. |

||||

| a young, largely unknown, former airmail pilot named Charles Lindbergh |

But other aviators, including Clarence Chamberlin, Richard Byrd, and a young, largely unknown, former airmail pilot named Charles Lindbergh, had made their intentions clear. It seemed probable that one of them would succeed in making the flight within the next few weeks. |

|||

|

Pinedo, of course, hadn't registered as a contender for the Orteig Prize. Participation in any competition, especially one involving a cash prize, was out of bounds for his goodwill tour. Besides, the range of the S-55, about thirteen hundred miles, would never have taken him to Paris without at least one refueling stop along the way. But there was another aspect to be considered. Public enthusiasm for the Orteig contest was rapidly approaching the mania level, and unless he wanted to see his achievements of the past four months eclipsed forever by the more glamorous feat on some other flyer, Pinedo knew that he'd better make his ocean crossing first. |

||||

|

Boarding their new plane, Pinedo and his companions took a few days to mop up their East Coast tour with stops at Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston, before doubling back to New Orleans, which would serve as a springboard for token coverage of the Midwest. From here they planned to soar up to Newfoundland by way of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Seaway. By May 21st, at the very latest, they expected to be eastbound over the Atlantic. |

||||

| The delay forced Pinedo to cancel a brief stop at St. Louis... |

Before reaching New Orleans, the Italians made a refueling stop at Pensacola, and Pinedo wired ahead to request that no receptions or festivities be prepared for him, since he planned to stay in Louisiana but a few hours. Constant rains had flooded the Midwest throughout the spring of 1927, and Santa Maria departed from New Orleans against yet another heavy thunderstorm, beginning its northward run over the swollen Mississippi on May 14th. Headwinds severely taxed the plane's fuel supply, and the Italians had to make an unscheduled stop at Memphis, passing the night there to wait out the storm. The delay forced Pinedo to cancel a brief stop at St. Louis, and the disappointed citizens of that city, who had lined the river banks under umbrellas in anticipation of the S-55's arrival, were given only a quick glimpse of the flying boat as it sped across the gray skies overhead. |

|||

|

Minutes later, Pinedo switched over to the Illinois River. Here he was met by squadrons of American military planes from Chanute and the Great Lakes Naval Center, which lined themselves up in honor guard formation and escorted the Santa Maria directly to Chicago's lakefront. A din of horns, bells, sirens, and whistles from the surrounding boats rose up with the cheers of thousands of Chicagoans as a Coast Guard tender pulled the plane in for mooring at the Chicago Yatch Club. The aviators stepped on shore and were literally mobbed by the city's Italians, who surged forward to greet them with embraces, kisses, and hearty slaps on the back. |

||||

|

That afternoon, Pinedo heard Mass at Holy Name Cathedral, and afterwards paid a visit to Cardinal Mundelein, who eloquently praised the flyer for his achievements. During a banquet that evening at the Palmer House, he concluded his speech by humorously noting that the absence of alcohol obliged him to postpone the pleasure of properly toasting Chicago. Within a very short time he would be back in Italy, and there, he pledged, he would lift a glass to the city. |

||||

| ...his impatience to get on his way was impossible to conceal. |

But the next day, Pinedo might have wondered if he'd ever get the chance to keep his promise. Crashing waves on a turbulent Lake Michigan drenched his plane's engines out of service, and one more day was lost in his race to get back to Rome. He passed the hours pleasantly, touring Chicago sites and attending a reception and dinner at the Italian Consulate. But though he joked that the delay gave him a rare chance to relax, his impatience to get on his way was impossible to conceal. |

|||

|

Before sunrise the following day, the Italians hastily checked out of the Drake Hotel and made their way back to the lake escorted by motorcycled police. At 7 o'clock, they were in the sky, tracing a great circle overhead to bid farewell to the hat-waving spectators who had come to see them off, then vanishing into the hazy, eastern horizon. |

||||

|

Foregoing earlier scheduled stops at Detroit and Buffalo, Pinedo cut across southern Michigan and veered to the northeast over Lakes Erie and Ontario. By the evening of May 17th, the Italians were in Montreal, where precautions for their safety were taken when anti-Fascists again voiced threats. No incidents occurred, and the aviators forged their way ahead against persistently inclement weather until they arrived at Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland on May 20th. Their North Atlantic crossing was finally at hand. |

||||

| ...or even caught sight of the Spirit of St. Louis as it passed over Newfoundland |

At 7:52 on that very morning, Charles Lindbergh hopped into his Ryan monoplane at New York's Roosevelt Field, and took off in the drizzling rain, pointing himself toward Paris. Had conditions been right, Pinedo might have heard the drone of its engine or even caught sight of the Spirit of St. Louis as it passed over Newfoundland on its way to the open seas. But at least for the moment, Pinedo was still the big name, and the Newfoundland Post Office was already putting its money on his success. That day, it issued the world's first commemorative stamp honoring an individual aviator, and on it was Pinedo's name. |

|||

|

The S-55's range made the Newfoundland-Azores-Portugal route blazed by the U.S. Navy planes in their 1919 crossing the logical path home, since it provided the essential, mid-way refueling point. But even under favorable conditions, it would be a tough and risky run. Harsh weather continued to prevail, but predictions of improving conditions encouraged Pinedo to set his departure for 2 am on May 21st. But when the hour arrived, sheets of freezing rain and violent gusts of wind repeatedly put his plane back down to earth. A few hours later, after a day and a half flight that instantly became a legend, Lindbergh touched down at Paris, completing the first, solo non-stop Atlantic crossing. And Pinedo still hadn't even gotten his plane in the air. |

||||

| By then, the tailwind that had helped pushed Lindbergh to glory had vanished. |

Not until 4 am the next morning, in fact, was he able to make a successful takeoff from the crashing waves off Trepassey Bay, and to do so he had to dump some of his precious fuel. Managing to pull the plane off the water by no means ended his bad luck. By then, the tailwind that had helped pushed Lindbergh to glory had vanished. Barely an hour in the air, dense fog swallowed the Santa Maria II, and by ten o'clock it was bucking furious, southeasterly headwinds that made fuel consumption skyrocket. While battling the elements, the Italians started drifting off course, and though they regained their bearings by early afternoon, Pinedo knew that they'd never reach the Azores before the gas tank was dry. |

|||

|

At that desperate point, they sighted the Portuguese fishing boat Infante de Sangres sailing below. Pinedo brought the plane down to the surface and signaled for assistance. The Italians explained their predicament, and the fishermen readily offered to tow the aircraft for the remaining two hundred miles to the Azores. |

||||

|

Since neither the plane nor the boat carried a radio, Pinedo's fate remained unknown to the rest of the world during these hours. That he had left Newfoundland and was long overdue at the Azores was all that was known. At Rome's Palazzo Venezia, Mussolini spent the night pacing before his telephone, unable to sleep until news of his aviators arrived. At ten the next morning, he was relieved to learn that a British steamship had sighted a schooner pulling what appeared to be a white seaplane southwest of the Azores. This was soon followed by a similar report from a Spanish ship, and the Italian steamer Superga was ordered to meet the Infante de Sangres and assume the task of towing the S-55 to port. An inspection at Horta Bay in the Azores revealed damages suffered by the plane in towing, and a week of repairs were required to make it airworthy again. When the work was done, the ever-concise Pinedo resumed his flight by returning to the spot where he'd been rescued by the Portuguese, and from there proceeded on his trip home. After stops in Portugal and Spain, he reached Ostia harbor, just west of Rome, on June 16th. |